The way we die is still trapped in the ‘60s

While ending one’s own life was no longer a crime, any assistance given to another person in ending their life became punishable by up to 14 years in prison, regardless of the circumstances. This law was introduced, ostensibly, to safeguard life, to protect potentially vulnerable people from abuse or coercion. But in one fell swoop it also criminalised acts of genuine compassion, preventing individuals from seeking help to end intolerable suffering caused by terminal illnesses.

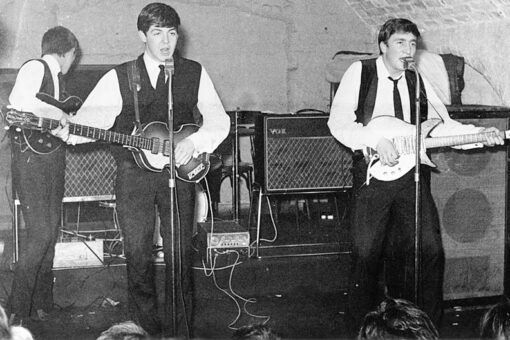

In the same year this law was introduced, JFK was sworn in as the 35th president of the USA, the Berlin Wall went up and the first human travelled to space. The assisted dying ban is older than the Rolling Stones, Songs of Praise and the mini-skirt. In 1961, racial discrimination was not yet prohibited by law, homosexuality was still illegal and women were unable to secure a legal abortion. There were only six women in the House of Lords and 25 women MPs.

Society has moved on, and yet the laws governing how we die remain in the dark ages.

As the House of Lords prepares to debate prospective assisted dying legislation for the first time in more than five years this autumn, it is time to take a step back and question whether the current law is really fit for the 21st century.

The UK prides itself on liberal, progressive values that are the hallmark of modern, civilised societies around the world, yet on end-of-life choice we lag dismally behind. Terminally ill citizens of ten American states, four Australian states, Canada and New Zealand are afforded the ability to die as they have lived – on their own terms – including determining the place, manner and timing of their death. In contrast, dying Brits are faced with an archaic set of choices.

Here, people suffering in their final months are forced to choose between enduring a traumatic death, travelling to a foreign land with more compassionate assisted dying laws, or taking matters into their own hands at home in often violent ways. Is this really the best we can do in 2021?

It is clear that the public and an increasing number of doctors and law-makers believe we can and should do better. Momentum for change is building right across the British Isles – in addition to the Lords’ debate this autumn, legislators in Scotland and Jersey will also deliberate on assisted dying this year. The time has come for a new standard of dying built on compassion, one that respects personal choice and autonomy while providing robust protection to those who do not want or qualify for this option.

Soon, we will look back on the assisted dying ban as a relic of the past, but until then terminally ill people will continue to suffer, loved ones will continue to be criminalised for acts of compassion, and healthcare professionals will continue to be prevented from offering the full range of end-of-life choices their patients want and deserve. Parliamentarians must act as a matter of urgency and ask themselves who or what they are prepared to defend: dying people, or a 60-year-old law.